As this is written ongoing is a nationwide politically inspired panic concerning not only some types of firearms but virtually all types of ammunition and even reloading components. As for smokeless powders and primers there isn’t much that can be done. Jacketed handgun bullets of all types are also going to be hard to come by for a bit. Our bullet factories are capable of only turning out so many in a shift and rifle shooters’ needs are also a significant factor in production.

Handgunners have a fall- back position. We can shoot lead alloy bullets. They work perfectly for all types of handgun (Very few handgun makers recommend their products not be fired with lead alloy bullets.) Right in the midst of all this hoarding and panic buying I don’t have a single bullet worry. In my vault are several score handguns chambered for 21 different cartridges. On shelves above my lead pot are bullet moulds suitable for handloading lead bullets. I have never lacked for handgun bullets since age 17.

To become an avid reloader of lead bullets there is one hump you must overcome. There exists in some places a news media inspired fear of lead. Lead does not give off death rays nor is it lethal if touched. Lead is harmful only if actually ingested into the body through the mouth and eyes or from a bullet shot into you and left there. In my strongly held opinion fear of lead alloy bullets is encouraged by anti-gun activists as another form of control.

When I started handloading, if you didn’t pour your own bullets you weren’t going to have any. Essentially the act of casting bullets is simple. Molten lead alloy is poured into a mould with cavities cut to specific dimensions. After a few seconds the alloy has solidified and when the mould is opened new bullets fall out. For those interested in starting bullet casting I recommend LYMAN’S CAST BULLET HANDBOOK, 4th EDITION. (I wrote 15 of the 18 informational chapters in it.)

Now let’s get into some details, handgun bullets can be divided into two categories: those for autoloaders and those for revolvers. I want autoloader bullets hard so they can withstand the rigors of being shoved out of a magazine, up a feed ramp and into a chamber. Also because autoloader cartridges have always been developed as jacketed bullet rounds, rifling in most stock pistols is relatively shallow. Hard bullets grip shallow rifling. Soft bullets skid on it.

On the flip side revolver bullets need to obturate, which means swell up. They do that in revolver chamber mouths upon firing and keep doing it upon entering the barrel forcing cone. No obturation means gas will leak by the bullet’s base, melting particles off and plating them inside the barrel. Very hard bullets resist obturation and result in worse leading than milder tempered ones unless fired at very high pressure levels. Revolvers as a rule have deeper rifling so softer bullets don’t skid when fired.

Lead alloy is rated by Brinell Hardness Numbers. By my standards anything over 15 is good for autoloaders and any alloy between 10 and 12 BHN is good for revolvers EXCEPT FOR SUPER HOT MAGNUM VELOCITY LOADS. For those then go back to the plus 15 BHN alloy. For the sake of comparison here are some common alloy BHNs: pure lead is about five. A mix of one part tin to 20 parts lead rates about 10, and linotype alloy as used in the printing trade for decades is about 22. I use linotype for semi-auto handguns and my submachine guns because I have a large supply of it. For revolver bullets traveling under about 1,100 fps I stick with 1-20 again because I keep a large supply of it.

Next is the question of bullet shape. That one is easy. My autoloading bullets are MOSTLY roundnose. Roundnoses have fed perfectly in every semi-auto pistol I’ve ever owned and usually give more than adequate accuracy. But it is not a rule carved in stone that roundnoses are the only pistol bullets that feed. My Kimber 1911 .40 S&W works just fine with semi-wadcutters.

Revolvers are also usually exceedingly accurate with roundnose bullets but revolvers will function fine with sharp cornered bullets. Wadcutters, semi-wadcutters and roundnose/flatpoints are all great revolver bullets.

Lead alloy bullet diameters are factors that sometimes get newcomers flummoxed. With jacketed handgun bullets the question of diameter is moot because the handloader has no control over the matter. You take what the factories make. For instance, 9mm bullets are universally .355 inch and .45 ACP bullets are .451 inch.

Lead alloy handgun bullets need be a mite larger – in general .001 to .002 inch over the size of jacketed bullets for the same caliber. When I cast my own from Lyman mould #356242 they are run through a .357 inch sizing die. In some 9mm pistols of modern manufacture .357 inch bullets may make cartridges too fat to chamber. Then .356 inch is the size. Most of my 9mms are vintage military types with generous chambers so I can get away with .357 size 9mm bullets. I didn’t get away with overly large .45 ACP bullets in one situation recently. On hand are a couple of Remington’s new 1911s. Following my bigger is better in regards to lead bullets I tried feeding them .452 inch cast bullets. One of the Remingtons digested them fine but the second one’s slide wouldn’t close completely. It worked fine with .451 inch bullets.

Of course revolvers have one other dimension to consider – the cylinders’ chamber mouths. Accuracy benefits if bullets fit chamber mouths within about .001 inch. Sometimes that’s just not possible. Here’s just one example: my 1990s vintage Colt Single Action .44-40 has .432 inch chamber mouths, yet its chambers do not accept rounds loaded with bullets larger than .428 inch. With the exact same handloads that particular revolver never groups as well as another Colt .44-40 with .429 inch chamber mouths.

Ok; once you have lead alloy bullets of the proper hardness, shape, and size for your handgun what special reloading techniques are required? Very few; cases are resized normally and when bullets are seated they should be crimped just as jacketed ones i.e. taper crimp for autoloaders and roll crimp for revolvers. (That’s generally speaking, but perhaps a topic for the future.)

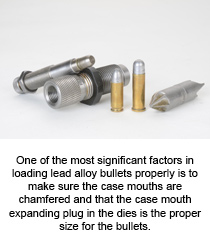

Where handloaders need give lead alloy bullets special attention is keeping them from being damaged when entering the case. First off, case mouths should be deburred. Case mouths left with sharp edges will peel slivers of lead from the bullets’ sides. That step need be done only once unless the case is trimmed somewhere along the line.

Also some attention should be given to the size of the expander plug in case mouth belling dies. Expander plugs sent with die sets the manufacturer assumes will most likely be used with jacketed bullets are a mite smaller than those die sets most likely used with lead alloy ones. Here’s an example: my RCBS 9mm Parabellum and .380 Auto dies have .351 inch expander plugs meant for .355 inch jacketed bullets but my RCBS .44 Russian/Special “Cowboy” dies expressly meant for lead alloy bullets have .428 inch expander plugs because they will likely be used with .430 inch bullets.

There you have it; don’t shun lead alloy handgun bullets or you may wind up with no bullets at all.

Photos by Yvonne Venturino

DISCLAIMER: All reloading data in this article is for informational purposes only. Starline Brass and the author accept no responsibility for use of the data in this article.